Cockatoos can tell when they need more than one tool to swipe a snack

Forget screwdrivers or drills. A stick and a straw make for a great cockatoo tool kit.

Some Goffin’s cockatoos (Cacatua goffiniana) know whether they need to have more than one tool in claw to topple an out-of-reach cashew, researchers report February 10 in Current Biology. By recognizing that two items are necessary to access the snack, the birds join chimpanzees as the only nonhuman animals known to use tools as a set.

The study is a fascinating example of what cockatoos are capable of, says Anne Clark, a behavioral ecologist at Binghamton University in New York, who was not involved in the study. A mental awareness that people often attribute to our close primate relatives can also pop up elsewhere in the animal kingdom.

A variety of animals including crows and otters use tools but don’t deploy multiple objects together as a kit (SN: 9/14/16; SN: 3/21/17). Chimpanzees from the Republic of Congo’s Noubalé-Ndoki National Park, on the other hand, recognize the need for both a sharp stick to break into termite mounds and a fishing stick to scoop up an insect feast (SN: 10/19/04).

Researchers knew wild cockatoos could use three different sticks to break open fruit in their native range of Indonesia. But it was unclear whether the birds might recognize the sticks as a set or instead as a chain of single tools that became necessary as new problems arose, says evolutionary biologist Antonio Osuna Mascaró of the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna.

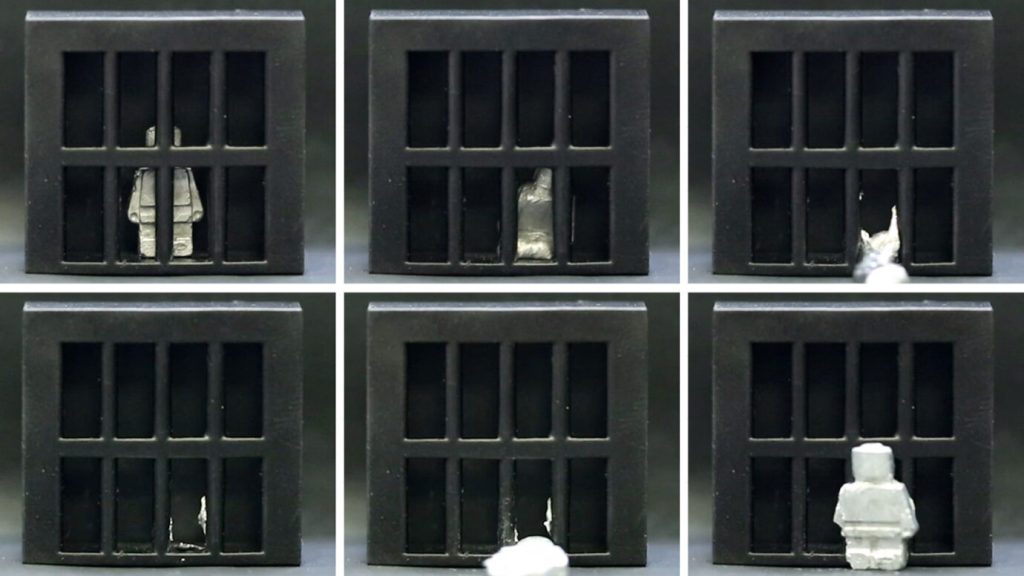

Osuna Mascaró and colleagues first tested whether the cockatoos could learn to smack loose a cashew placed inside a clear box and behind a thin paper barrier, akin to a chimpanzee’s hunt for termites. Six out of 10 cockatoos reliably knocked the nut out of the box using a pointy stick to poke through the membrane and a plastic straw to fish for the cashew.

Two birds managed the task in less than 35 seconds on their first try. Both — a male named Figaro and a female named Fini — are experienced tool users, Osuna Mascaró says.

Figaro, Fini and three fellow cockatoos were more likely to use both stick and straw only when the box had a paper barrier inside. If the team removed the barrier, the birds selected the straw instead of the stick as their tool.

Even when the birds had to walk or fly to reach the box, the birds brought along both tools every time the box had a barrier. If there was no paper, the cockatoos usually brought only one, a sign the cockatoos recognized when they needed their entire tool kit to swipe a snack.

Three of the birds even learned to put the stick inside the straw to carry both at the same time. That made for more efficient transport, meaning the birds didn’t have to make two trips and waste energy. Two birds, Kiwi and Pippin, transported both tools together every time the box had a barrier. Kiwi rarely brought along both tools if there wasn’t paper, and Pippin did so half as often.

Trading off which tools to bring may have to do with strength. After Figaro learned to combine transport, he grabbed both tools in 16 out of 18 trials. That may be because he’s one of the stronger birds in the group, Osuna Mascaró says. For him, grabbing both tools at once isn’t a big deal. Kiwi and Pippin, on the other hand, are weaker than Figaro.

Cockatoos raised in the lab probably display more abilities than a wild bird might use on an average day, Clark says. “Nevertheless, this means they can do it,” she says. “That doesn’t mean that the wild adult male … can do the same thing as Figaro. But he would have probably been capable of doing that had he been raised like Figaro.”