Post-stroke shifts in gut bacteria could cause additional brain injury

When mice have a stroke, their gut reaction can amp up brain damage.

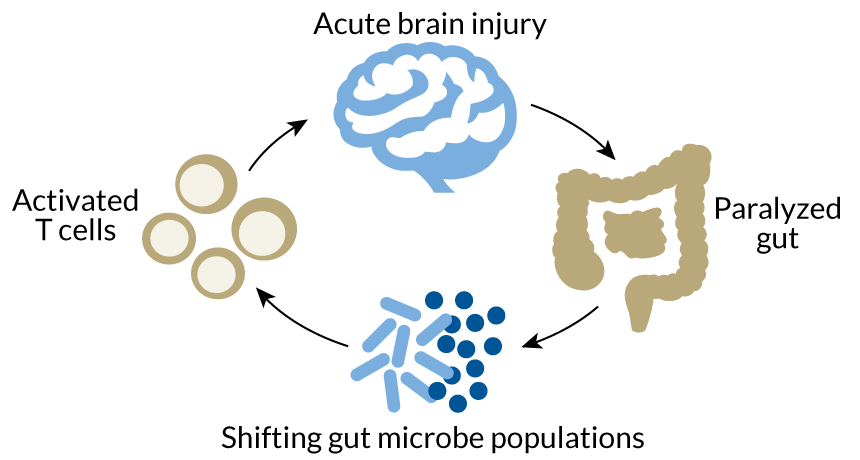

A series of new experiments reveals a surprising back-and-forth between the brain and the gut in the aftermath of a stroke. In mice, this dickering includes changes to the gut microbial population that ultimately lead to even more inflammation in the brain.

There is much work to be done to determine whether the results apply to humans. But the research, published in the July 13 Journal of Neuroscience, hints that poop pills laden with healthy microbes could one day be part of post-stroke therapy.

The work also highlights a connection between gut microbes and brain function that scientists are only just beginning to understand,says Ted Dinan of the Microbiome Institute at the University College Cork, Ireland. There’s growing evidence that gut microbes can influence how people experience stress or depression, for example (SN: 4/2/16, p. 23).

“It’s a fascinating study” says Dinan, who was not involved with the work. “It raises almost as many questions as it answers, which is what good studies do.”

Following a stroke, the mouse gut becomes temporarily paralyzed, leading to a shift in the microbial community, neurologist Arthur Liesz of the Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research in Munich and colleagues found. This altered, less diverse microbial ecosystem appears to interact with immune system cells called T cells that reside in the gut. These T cells can either dampen inflammation or dial it up, leading to more damage, says Liesz. Whether the T cells further damage the brain after a stroke rather than soothe it seems to be determined by the immune system cells’ interaction with the gut microbes.

Transplanting microbe-laden fecal matter from healthy mice into mice who had strokes curbed brain damage, the researchers found. But transplanting fecal matter from mice that had had strokes into stroke-free mice spurred a fourfold increase in immune cells that exacerbate inflammation in the brain.

Learning more about this interaction between the gut’s immune cell and microbial populations will be key to developing therapies, says Liesz. “We basically have no clue what’s going on there.”